Have you ever struggled to follow a conversation at a party? If listening and piecing together the conversation is a consistent problem, you might be suffering from auditory processing disorder (APD).

The term APD describes several disorders that result in a breakdown in the listening process. It is most common in primary school, affecting more than 5% of children.

A person with auditory processing disorder usually has normal hearing, which means they can detect very soft sounds. But their difficulty is in how they actually listen, or what they do with what they hear.

They have trouble separating competing sounds and distinguishing between similar sounds. Children with APD may also struggle to make meaning of information when words or other auditory signals are missing. These listening difficulties are particularly apparent in noisy environments, such as classrooms.

Why is it a problem?

Today’s classrooms are typically large, interactive spaces designed to engage children and promote learning. These are also noisy spaces that challenge the listening abilities of many children.

As noise levels fluctuate, listeners need to fill in small gaps in what was said. A child with an auditory processing disorder needs to do this much more often than their classmates, using up lots of energy. As a result they will quickly become tired.

Another problem typically reported with APD is difficulty following instructions and concentrating, especially in a noisy environment. If left untreated, these difficulties can impact on a child’s ability to learn.

Reading deficits, for instance, are the leading reason for referral to an audiologist for an APD assessment. Research shows it is highly likely a child with reading deficits will also have an auditory processing disorder.

These literacy and learning deficits can remain in place throughout the child’s education journey. Although the listening skills may catch up, the missed learning may not.

How is it diagnosed?

Auditory processing disorder is usually diagnosed by a hearing professional called an audiologist. A collection of tests is used to measure listening skills. These may include repeating sentences that become softer against background noise, which measures how well the child can separate the targeted speech from the noise.

Another common test involves a child receiving different signals in each ear, such as numbers, and being asked to repeat them both. This measures the ability to listen to competing signals.

Due to outcomes in recent research, tests that assess a child’s attention, memory and intelligence have been included in the diagnosis of APD. But audiologists also need to be careful not to confuse auditory processing disorder with other disorders, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder, which can show the similar behaviour of poor listening.

Attention, memory and intelligence tests are now routinely performed in many hearing clinics throughout Australia and research is identifying better and more age-specific diagnostic tests.

All this has greatly improved the ability of audiologists to more accurately determine the main cause of a child’s listening difficulties.

What causes APD?

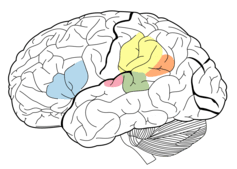

The process of listening that develops throughout childhood involves growing pathways of the central auditory nervous system. Although the exact cause of auditory processing disorder is unknown, there is increasing evidence that developmental delay is the likely cause for many children.

Some children will be able to catch up over time but in others, the disorder may last into adulthood. This means children with APD need to better develop and strengthen the neural connections and pathways required for complex listening.

There is also evidence children who have a middle ear infection, resulting in glue ear (or sticky fluid in the ear), may later develop APD. This is assumed to be due to the fluctuating hearing loss associated with glue ear that disrupts the cues needed to develop listening skills.

How is APD treated?

The appropriate treatment plan to help a child with auditory processing disorder will depend on the type of deficit diagnosed.

In classrooms, devices can be used to improve sound signals. A personal frequency modulation device, for instance, can transmit sound directly from the teacher to a receiver worn by the child.

Many researchers are focusing on developing training programs that target the main cause of listening difficulties. These usually aim to strengthen listening skills and associated neural pathways using specialised software programs that provide listening tasks and typically up the difficulty as the child’s skill improves.

Children can also be trained to strengthen language comprehension and memory by a speech therapist, which will assist with listening.

Listening is a complex behaviour, involving many skills, and we still need to improve our ability to identify those at risk before learning becomes affected. It is very likely there are specific skills we have not yet identified, or are able to measure, that may significantly contribute to listening ability. The challenge for researchers and clinicians is to work out what they are.

Dani Tomlin receives funding from the HEARing CRC.