A Michigan surgeon invented an apparatus that he believes tricks the brain into thinking the stomach is full.

Bonnie Lauria was miserable. She was subsisting on liquids and a handful of foods her stomach could handle. Ever since she’d undergone gastric bypass surgery in the ’80s, foods like meat and bread that went down her throat in a lump would come right back up. “I knew where every bathroom was in every restaurant in the state,” Lauria says from her home in West Branch, Michigan. “It was horrendous.”

During gastric bypass surgery, the stomach is reduced to about the size of a walnut and attached to the middle of the small intestine. Lauria’s complications from the surgery weren’t normal, so she went under the knife a second time. Still, her condition didn’t change. She switched doctors several times, but no one could help. Eventually, someone recommended bariatric surgeon Dr. Randy Baker in Grand Rapids in 2004.

Baker ran some tests and saw that the spot where Lauria’s walnut-size pouch met her small bowel was tightening. Previous doctors had tried to widen the passage so that food could pass through, but the stricture had returned. Complicating Lauria’s condition were those multiple surgeries, which left so much scar tissue that operating again would be too difficult and too dangerous.

Dr. Randal S. Baker. Erin Kirkland / BuzzFeed News

Baker was at a loss. Then he started thinking about esophageal stents. Just like a coronary stent keeps an artery open, an esophageal stent holds the esophagus open and is often used in patients who have difficulty swallowing. What if one of those could prop open the small bowel too?

As far as Baker knew, no one had ever attempted a procedure like that before. But Lauria was out of options, so Baker told her his strategy. She agreed; he inserted the stent and hoped for the best.

“She came back to my office two weeks later and said, ‘Dr. Baker, I’m feeling great. I can eat sloppy Joes!’” Baker says. “Here’s a lady who could only do liquids, and now she can eat solids. And she’s losing weight.”

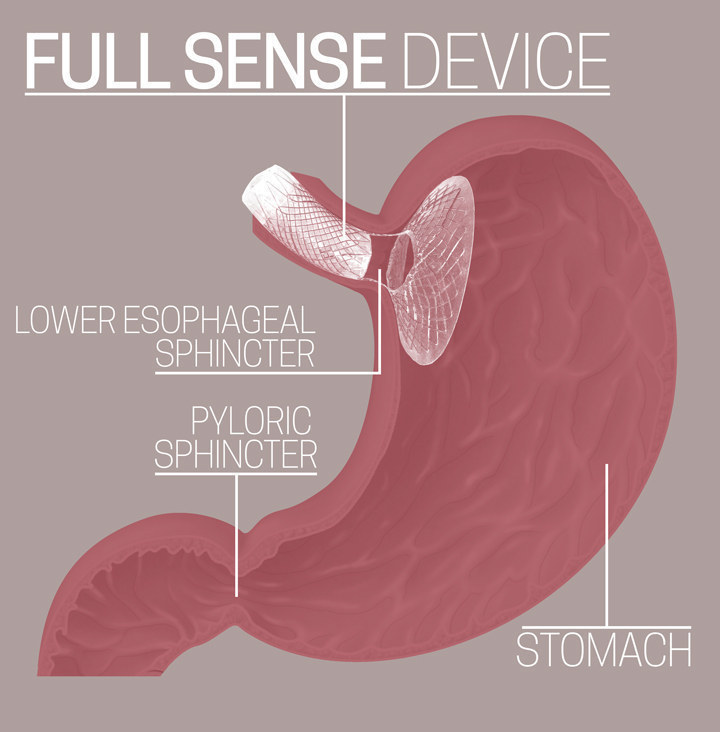

Lauria didn’t have an explanation; she told Baker she simply wasn’t hungry anymore. Baker wondered if he and other bariatric surgeons had been going at it all wrong. The stent, he theorized, was putting pressure at the top of Lauria’s pouch and sending signals to her brain saying, “I’m full.” It was doing what food does, but without actual food. Which raised some questions: What if we don’t need invasive surgeries that cut away portions of the stomach and rearrange the digestive tract and intestines? What if all we need is a device that puts pressure near the top of the stomach?

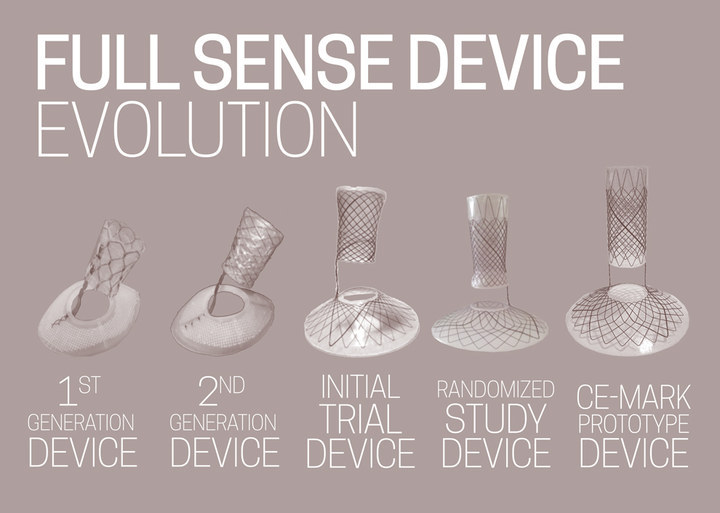

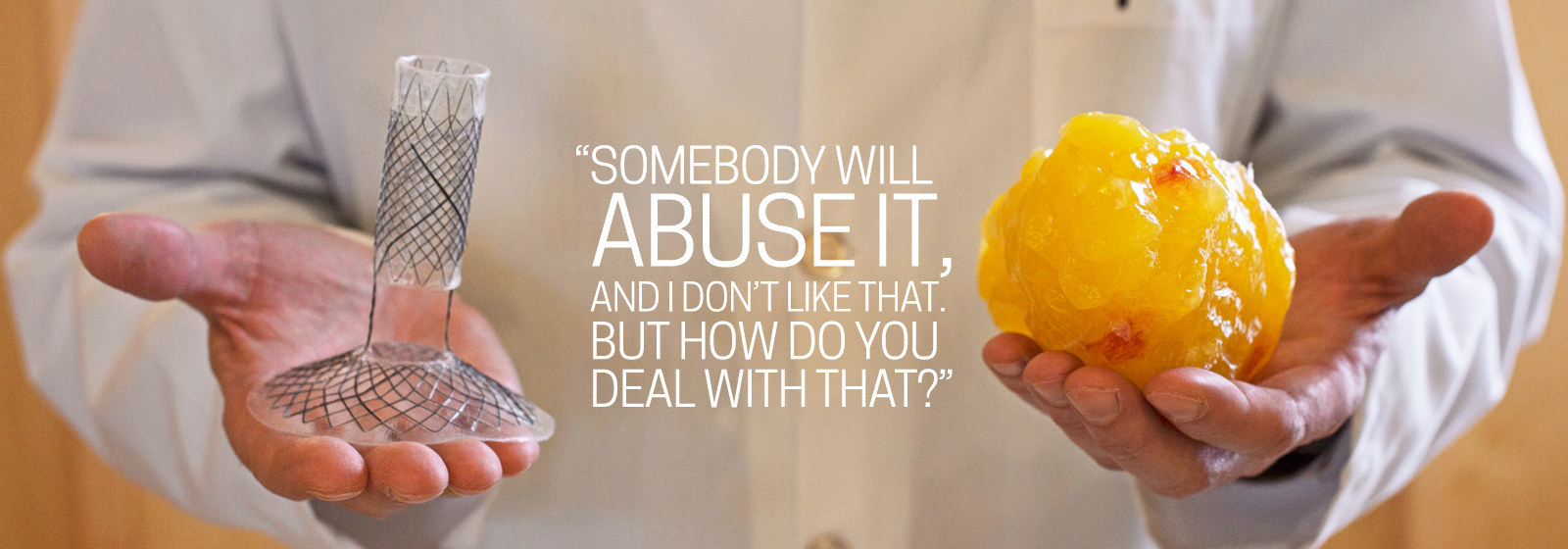

Baker set out to test his hypothesis, teaming up with a former product specialist from W.L. Gore (creators of Gore-Tex) and two surgeons at his Grand Rapids practice to create the Full Sense Device — a nitinol wire-mesh funnel coated in silicone that can be inserted through the mouth and placed in less than 10 minutes. Current plans would allow the device to remain for up to six months before removal, though in the future that time may be longer. In the company’s trials, every patient implanted with the device lost weight and continued to lose weight until the device was removed. Baker calls the phenomenon “implied satiety.” At six months, average patients lost 75% of their excess body weight — significantly more and at a faster rate than any bariatric procedure, and all, Baker says, with no “severe adverse side effects.”

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimates that 160 million Americans — nearly half — are overweight as indicated by their body mass index, which is calculated from a person’s height and weight. (A BMI between 25 and 29.9 is considered overweight; 30-plus is obese.) Of those people, 24 million are estimated to be morbidly obese, meaning they have a BMI over 40 and are at higher risk for serious, life-threatening illnesses, including heart disease, diabetes, degenerative arthritis, and cancer. Bariatric surgeries can and often do lead to impressive weight loss, yet only 1% of obese Americans opts for the invasive and costly procedure — usually $20,000 to $30,000. (Rex Ryan, Roseanne Barr, Carnie Wilson, Al Roker, Chris Christie, Randy Jackson, and Star Jones are reported to be among the 1%.)

“There are a bunch of things that contribute to that,” says Randy Seeley, an obesity researcher and professor of surgery at the University of Michigan. “One is the ick factor — ‘someone is going to chop up my GI tract.’ Some of it is cost — it’s still not universally covered. Third is stigma. The implication is that it’s the easy way out — you’re cheating somehow by taking that option — which goes to our societal biases about obesity.”

Dr. Baker has come up with a nonsurgical device that he says will enable obese patients to lose substantial weight, and at a fraction of the cost of surgery — in the neighborhood of $5,000 at an outpatient center. A company claiming to have found a simple solution to drastic, easy weight loss is, of course, nothing new; in fact, it’s big business. (See: late-night infomercials.) Some surgeons and researchers are skeptical of Baker’s pressure theory, and at least one patient experienced chronic acid reflux after the device was inserted. But more than 10 years after the eureka moment, Baker is hopeful that doctors in Europe could begin using the Full Sense Device this year and in Canada and Mexico soon after. Americans will have to wait longer; Food and Drug Administration approval is unpredictable and likely still years away. Baker’s concern, though, is that the Full Sense Device might work too well. If it’s effective, easy, and cheap, what’s to stop people from abusing it?

“When this hits the market, there’s not going to be just 10,000 to 15,000 people having it,” says Fred Walburn, president and sole employee of Full Sense Device’s parent company, BFKW. “There’s going to be hundreds of thousands. Millions per year.”

BSIP/UIG Via Getty Images

At Grand Health Partners, the Grand Rapids practice Randy Baker shares with other bariatric surgeons, including his business partners Dr. James Foote and Dr. Paul Kemmeter (the F and K in BFKW), the hallways are extra wide and the doors are oversize. Waiting-room chairs are huge. Even the toilets are bigger and mounted to the floor (not the wall) to better accommodate obese patients. Everything is designed for the comfort of patients who are used to being uncomfortable wherever they go.

On a fall afternoon, Baker shows me into Grand Health Partners’ endoscopy suite, where I watch him put a scope down patients’ throats to investigate postoperative acid reflux and take preoperative biopsies.

In black slacks and a striped button-down, Baker, 50, taps on his iPad while nurses sedate the patients. Despite his 6-foot-5-inch frame, he’s not an imposing figure. With tidy, graying hair and black, wire-rimmed glasses, he has the kind but serious air of a high-school chemistry teacher. When he explains that he discovered something no one else had thought of, he says it with zero dramatic flair. The most animated version of Baker shows up when he explains something, and I respond in a way that communicates an understanding of the concept. “Exactly!” he says.

Each endoscopy is quick — 10, maybe 15 minutes. Patients aren’t in a deep sleep; inserting the scope only requires sedation as opposed to the general anesthesia that is often needed for surgery. Some of these patients will see Baker again in the coming weeks for a 60- to 75-minute sleeve gastrectomy, his preferred bariatric surgery. Such procedures are most often a last resort for morbidly obese patients.

Later that night, as I’m sitting across from Baker at Kitchen 67, a chic Grand Rapids bistro with rows of pulsating screens on the ceiling and iPads in the booths, Baker prays for our meal and our families. He’s the father of nine, an elder at his church, and the board president of Zion Christian School, where he led the charge in revamping the entire curriculum. He and his family used to sing and tour in a Southern gospel group. Baker recommends the burgers, noting that I should feel free to build my own burger instead of choosing one of the restaurant’s signature varieties. “I don’t like categories,” he says.

Once I finish my cheeseburger, Baker takes out his MacBook and queues up a video of a bariatric surgery. An extreme close-up of white-and-red gut gore appears on the screen, followed by a harmonic scalpel that looks like a serrated pincer, which begins squeezing and cutting masses of surprisingly tough, glistening white fat from a pinkish mass that Baker tells me is the stomach — “the second biggest I’ve ever seen.” I glance around the restaurant and ask him if we can turn the screen a bit so as not to ruin someone else’s dinner.

Even though he’s performed thousands of bariatric surgeries, Baker hasn’t lost sight of the harsh, invasive nature of what’s happening in that video. He explains that he spends most of each surgery attempting to gain access to the stomach. Obese patients have so much fat, not to mention an enlarged stomach and liver, that the workspace is cramped. The flimsy spleen is close by, as well. Brush it ever so slightly and it’ll bleed. Plus, there are vessels hidden in the fat. If a surgeon hits a vessel that starts to bleed, it sets off a frantic search to find the source.

“I had a patient who died once from a different surgery because there was an abnormal vessel in an abnormal place, and it started bleeding,” Baker says. As surgeries go, these are relatively safe. Mortality rates for three common procedures — gastric bypass (also called Roux-en-Y), vertical sleeve gastrectomy, and gastric banding — range from 0.14% to 0.03%, which are lower than gallbladder removal or hip-replacement surgery mortality rates.

“This one started to bleed a little bit,” Baker says, pointing to a spot on the screen. “I’m guessing where the bleeding is, but I can’t tell. Can you tell where the bleeding is?” I’m clueless. He closes the computer. “This is the best we have right now,” he says. “When I’m operating on big patients, I’m thinking, This would be a piece of cake if we popped in a Full Sense Device. The biggest highway to the stomach is not through the abdomen. It’s through the mouth!”

Photograph by Erin Kirkland for BuzzFeed News

Though the concept of hunger may seem simple, it isn’t, nor is it understood entirely. Scientists haven’t pinned down exactly how the stomach communicates with the brain. The interaction between gut hormones and the nervous system is key — ghrelin and leptin, for instance, act on neural components of hunger — but there isn’t a complete set of answers for how the gut regulates appetite.

There’s also no consensus as to how or why bariatric surgery often leads to dramatic weight loss and diabetic improvements (or why sometimes it doesn’t). Most bariatric surgeons were taught that the procedures lead to weight loss through restriction and/or malabsorption, and many still hold fast to those two explanations. The restriction theory says that the surgeries lead to weight loss by limiting the amount of food the body can hold. Malabsorption — when something is bypassed to reduce absorption of calories — is also thought to play a role in gastric bypass. But research from the past few years suggests that there are, at the very least, more things going on.

What makes a gastric bypass patient eat less, Baker theorizes, is that it takes less food to put enough pressure on the stomach so that it sends neurological and hormonal signals to the brain saying, “I’m full.”

“People used to think satiety was on or off,” Baker says. “You’re hungry or you’re not hungry.” But Baker says it’s actually a continuum. When there’s nothing in the stomach you have hunger, then you progress to “not hungry,” then levels of fullness, then nausea, then vomiting. “The more pressure you put on,” he says, “the higher you get up that cycle.”

Randy Seeley, the University of Michigan researcher, has a different take. “It’s very clear that restriction and malabsorption have little to do with how surgery works,” says Seeley. His research points instead to the importance of gut bacteria — particularly the hormonal action of bile acids — after surgery.

While Seeley says he’s willing to be convinced by data, he’s no less skeptical of Baker’s pressure theory. There are stretch receptors in the stomach, and the nerves there do respond and generate a signal when you stretch those receptors. But he wonders how much that matters to body weight. “For [Baker] to say that it’s not about restriction is getting outside of a surgeon’s box,” Seeley says. “But to say that it’s pressure, for me, is not changing the box very much.”

Baker agrees that gut bacteria and hormones are important, but thinks the stomach’s upper portion is the gut’s brain, which sets other processes in motion. Still, many questions remain regarding the roles restriction, malabsorption, pressure, hormones, and nerves play in bariatric surgery, and the answers will likely determine whether the Full Sense Device is a legitimate, long-term alternative to weight-loss surgery.

“When we have all those answers, we can put surgeons out of business,” Seeley says.

DEA PICTURE LIBRARY/De Agostini / Getty Images

First came the animal studies. Between 2005 and 2008, BFKW held five studies using beagles, which are less prone to ulcers than pigs and have an esophagus similar in length and width to a human’s.

“We ended up having 1% total body weight [loss] per day,” Baker says of the final six-week beagle study. “In the protocols, they said if you get to 20% weight loss, you euthanize the animals. The vets came to us and said, ‘We’re at that 20% rate. Most of the time, animals that lose this weight will become lethargic. These animals are wagging their tails. We’ve never seen anything like this. They’re starving themselves to death, and they’re happy about it.’”

The dogs were actually losing too much weight, so the device was later softened. Also, in a few of the dogs, the device fell out. “The instant they migrated, the dogs were hungry,” Walburn says. (Walburn had quit his job at Gore and moved to Grand Rapids to work full-time on the Full Sense Device.) “They ate every bit of food that was in their cage.”

BFKW’s patient trials have been overseen by Baker, Foote, and Dr. Jorge Trevino, a surgeon in Cancun. The first six-week study in November 2008 was limited to three patients who were fitted with the device and told to go on a liquid diet for one week, then eat normally. They also met with a nutritionist. All three lost significant weight.

Just as the beagles had been, the initial trial patients “were just happy,” Walburn says, explaining what they believe is going on: “Because of the pressure on the top of the stomach, the body does not think you’re dieting. It thinks you’re full. It does not reduce the metabolism like what happens when you go on a diet.” In other words, the body doesn’t think it’s being starved for nutrition.

After making some tweaks, BFKW did a randomized controlled trial, which is the gold standard for clinical trials of drugs and medical devices. The randomized controlled trial was three months long and involved a relatively small sample of 18 patients, six of whom were in the control group and received no treatment. At three months, the control group had 15% excess weight loss compared with 42% in the group that had the device. BFKW then did a “crossover trial,” taking three of the patients from the control group and fitting them with the device.

“We put the device in them, and boom — if you compare that to when they thought they had the device but they didn’t, there’s a clear, statistical difference,” says Baker, who indicates that every patient — about 110 of them at this point — in the company’s various trials has lost weight and continued to lose weight with the device in place.

In a taped interview in Mexico, 41-year-old primary-care physician Manuel Perez explains in Spanish that the stress of studying medicine caused him to gain weight and eventually develop diabetes. His weight peaked around 285 pounds. After injuring his back, he couldn’t exercise much, and going to a nutritionist didn’t help. (“Mexican food is very delicious, so I couldn’t continue with the diet adequately,” he says.) Once fitted with the Full Sense Device in Cancun, Perez says he could control his diet better and he didn’t spend as much money on food. He lost 46 pounds in six weeks, and his diabetes and high blood pressure disappeared. His back pain went away too.

“Before I wanted to fill myself,” Perez says. “Now I eat very little.”

Not everyone’s story is as rosy as Perez’s, though. When I spoke to 49-year-old Cancun patient Luz del Carmen Gabriel, who had her Full Sense Device removed in January, she complained of severe acid reflux and nausea for the four months the device was in place. “It was uncomfortable when I slept,” Gabriel says. “I had to sleep sitting almost.”

Baker says Gabriel’s reflux was directly related to her size. She’s 4 feet 8 inches tall, which means she has a shorter esophagus than the average patient, and right now there’s only one size of the Full Sense Device. In the future, Baker hopes to have several sizes customized to a person’s height.

Gabriel says she wouldn’t necessarily recommend the Full Sense to others because of the reflux she experienced. “I got it bad,” she says. “Other patients didn’t get it at all.” But she’s satisfied with her weight loss from the device, which worked better than the pills and diets she’d tried. She ate “much less,” she says. Last summer Gabriel had a BMI of 32, and now she’s down to a BMI of 24, putting her in the normal, healthy range. She lost nearly 40 pounds, which means, because of her small stature, she achieved more than 100% of her excess body weight loss.

“Of course it was worth it,” she says. “I feel more flexible. I feel more comfortable in my clothes … I feel better when I see myself. I feel good.”

BuzzFeed News

Baker and his partners are submitting the device for CE mark certification, which would grant approval for use throughout Europe, a process that is typically cheaper and more expedient than the FDA process. Also, the FDA says it requires a device to be both safe and effective, whereas the CE mark focuses only on safety. According to this model, as long as the Full Sense Device is safe, if no one loses weight with it, doctors will stop using it and patients won’t request it.

“We have six or seven centers identified and ready to go in Europe,” Baker says. “These are doctors who have a history of research — top-notch doctors.”

One of those is Shaw Somers, known in the U.K. as the bariatric surgeon on reality TV shows The Food Hospital and Fat Surgeons. Somers met Baker at a surgical conference in Istanbul in August 2013.

“There’s always a dose of skepticism when someone comes out with a claim that something works as well as a major intervention,” Somers says. “Most of the other implantable devices we use and have experience with aren’t as good.” But Somers, who doesn’t have a financial stake in the product or parent company BFKW, believes this one is different. “The Full Sense Device ticks all the right boxes,” he says. “It’s effective, easy to take in and out. There’s nothing out [there] to give it a run for its money.”

Since the U.S. doesn’t allow human trials unless it’s part of the FDA’s approval process, all of the Full Sense patient studies have been conducted in Cancun. Somers expects a call this year to head down to Mexico for training on insertion and removal of the device, and he’ll use that experience to put together a package of care at his own center. Baker and Somers say these “centers of excellence” are key to bringing the Full Sense Device to market. They will be equipped with resources similar to a practice like Baker’s Grand Health Partners, which includes dietitians, exercise physiologists, and behaviorists who specialize in bariatric psychology. The practice has its own store stocked with recommended (and GHP-branded) foods.

“It’s not, ‘Let’s just pile them high and sell them cheap,’” Somers says. “No device will work simply by implanting it without some type of instruction and modification of lifestyle. You need to manage patients in the medium term and longer term. What this industry does not need is a quick fix.”

Baker is fairly optimistic about the timeline and likelihood of FDA approval, especially after the approval in January of EnteroMedics’ Maestro System — the first medical device OK’d to treat obesity since 2007. That surgically implanted device is similar to a pacemaker, sending electrical pulses to the vagus nerve, which plays a role in the stomach’s communication with the brain. Headlines touted the “appetite-zapping implant” and even conspiracy theorist Alex Jones got in on the action, using the approval to decry the “deadly secrets of a hackable fat chip.” But there’s a question of how well the device works: Patients in a yearlong clinical trial did lose weight, but the 156 patients who received the device lost only 8.5% more of their excess weight than the 76 patients who were given a placebo implant.

This isn’t the first time a company has developed a stomach pacemaker. In 2005, the Wall Street Journal reported that “a new wave of implantable stomach devices could transform the way doctors approach obesity,” focusing particularly on the Transcend gastric stimulator, often referred to as a “gastric pacemaker” because, like the Maestro system, it sends electrical pulses to the stomach in hopes of regulating appetite. Medtronic, one of the world’s largest medical-device companies, purchased Transcend’s parent company for $260 million in 2005. But trials didn’t show a significant difference in weight loss between those who had the device implanted and those who did not. Transcend is still available in Europe as a treatment for obesity, but the FDA never approved it.

Despite similar doubts over the efficacy of EnteroMedics’ Maestro system, last summer an advisory panel decided the potential benefits of the device outweighed the risks, and the FDA followed suit with its approval. The high expectations for another questionably effective gastric pacemaker — which will cost between $15,000 and $30,000, about the same price as bariatric surgery — shows just how hungry the FDA, medical-device companies, and the general public are for an obesity-fighting alternative to bariatric surgery. And more endoscopic devices — balloons, fillers, liners — are on the way. One in the pipeline is GI Dynamics’ EndoBarrier, a liner placed at the beginning of the small intestine that was approved in Europe and is undergoing clinical trials in the U.S. In a previous trial, average excess weight loss with the EndoBarrier was 19% after three months — better than Maestro or Transcend, but not as impressive as BFKW’s studies.

Dr. Baker with Fred Walburn, president of BFKW Erin Kirkland / BuzzFeed News

Fred Walburn, president of BFKW, is more cautious than Baker about FDA approval for the Full Sense Device. He estimates the company won’t even begin the FDA process for three or four years. Walburn thinks the Full Sense Device could make the FDA nervous, but for precisely the reason you’d think it shouldn’t make a regulatory agency nervous. “If you’re a regulatory person, and everything you’ve done looks great,” Walburn says, “but there’s some tiny thing we’re missing, we’re not going to miss it in 1,000 patients. There’s gonna be a million people. If we made a mistake in approving it, we’ll get hauled in front of Congress.”

“That’s the big issue,” he says. “If it wasn’t [as] effective, and it would have a smaller market potential, it would be easily approved.”

Mary McGuire Photograph by Erin Kirkland for BuzzFeed News

Around 2009, Mary McGuire was watching TV with her husband when the local news ran a segment about Baker and the Full Sense Device. “I just looked at my husband and said, ‘Oh my gosh. This could be what I’ve been looking for,’” McGuire says. McGuire is 5 feet 5 inches and 291 pounds.

When McGuire was young, her mother would make doughnuts at home. The warm dough coated in cinnamon and powdered sugar was a special treat, though — not something they did all the time. When McGuire was just 7, her mother, a dietitian, died of pancreatic cancer. “Back then, you just kind of dealt with it,” McGuire says. “I never really had anyone to talk to about it.” Her father, now a single parent, would buy himself treats for his brown-bag lunches for his workweek: “He would take a paper bag for the week and have it full of sweets, and he would hide it up in the cupboard,” McGuire remembers. “He thought he was hiding it, but we all knew where it was. I would get home from school before he did, so I would get up on the chair to get into the cupboard and eat some cookies. When I lost my mom, that was my comfort food.”

McGuire, 53, still loves sweets: chocolate, cake, cookies, doughnuts. “If I get bad news about something, I’ll go to food,” she says. “Or happy too. A lot of times it’s boredom. A lot of times it’s stress. Some people pick up a cigarette. I pick up food. It comforts me. It relaxes me.”

Everything else she had tried either didn’t work or helped only temporarily: Weight Watchers, Slim-Fast, South Beach, Overeaters Anonymous, TOPS (Taking Off Pounds Sensibly), and Adipex, an appetite suppressant. Adipex helped her get down to 230, but she slowly gained it all back. None of the diets or portion-control strategies combined with exercise left her feeling satisfied. “I don’t get that full feeling,” she says. “That’s what I’m looking for. I want that sensation.”

McGuire emailed Fred Walburn after watching the TV segment, and ever since she’s been checking the company’s website for updates on the Full Sense Device. She’s convinced it’s the best solution for her. “It’s just so promising,” she says. “It makes sense to me.”

McGuire speaks about the piece of silicone and wire like it’s her destiny and last great hope. She goes to a pain clinic for pinched nerves in both her legs and struggles with high blood pressure, high cholesterol, sleep apnea, and edema. “I told my doctor the other day I feel like a beached whale,” she says. “I don’t want to be this big again. It’s awful. I hate it.”

Despite her desperation, McGuire won’t entertain the notion of bariatric surgery even for a second. A breast cancer survivor, she’s already had to endure more than 20 surgeries. But she can feel the clock ticking. “I know what my future holds if I don’t do something,” she says. “It’s not gonna be good.”

Photograph by Erin Kirkland for BuzzFeed News

Even if the Full Sense Device is approved and becomes an alternative to bariatric surgery, the question remains as to whether it’ll be able to provide lasting weight loss. Dr. Steven Bowers, a surgeon with the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, says the device is interesting, but he puts it in the same group as any other temporary, endoscopic weight-loss device. “It’s not astonishing that you can get the weight off people,” Bowers says. “The tricky part is the weight maintenance afterwards.”

Researcher Randy Seeley has similar concerns. “I’d be willing to bet a lot of money that when you take it out, people will gain the weight back,” Seeley says. “People want to think they’ll be so happy as a lean person that they’ll learn to be lean. And therefore, once they experience what it’s like to be leaner, they’re gonna stay lean. And that just doesn’t happen. There’s a reason why there’s no reunion shows for all the people who’ve been on The Biggest Loser.”

Baker acknowledges there will always be recidivism, but the ability to start over at an obese patient’s optimal weight is significant. And he maintains that no other weight-loss option currently available can match the Full Sense Device. “Nothing we have delivers 100%,” he says. “It is true — if patients want the best chance of keeping the weight off, they need to learn how to exercise and do all these other things right. But that’s true for everything. That’s true for surgery.”

Baker is less concerned about the device working than it working too well. Remember the beagles who were starving themselves to death and happy about it? What if irresponsible doctors allow overeager patients to lose unhealthy amounts of weight? What if this device becomes a new fad diet? “Somebody will abuse it, and I don’t like that,” Baker says. “But how do you deal with that?”

After Baker and his team safely removed the Full Sense Device from 10 more patients this month in Cancun, BFKW achieved “design freeze,” meaning the company is done tweaking (for now) and can move forward with the remainder of CE mark submission. Sometime this year, Shaw Somers and other surgeons from around the world will head to Mexico for training. As Walburn finishes the European approval process, he also has to keep the horse blinders on Baker, who’s already sketching out adjustable and absorbable versions of the device — ones that would potentially allow patients to keep the device in place for more than six months and could be tailored to each patient’s body type, whether morbidly obese or just overweight. “Randy is a chess player,” Walburn says. “He’s thinking two or three moves ahead. I don’t want him to stop, but I have to stay focused. I just tell him, ‘Write it down.’”

Bonnie Lauria hadn’t realized how far Baker had come in bringing his device to market until we spoke. “If it wasn’t for him, I’d still know where all the bathrooms in every restaurant are,” she says. “He saved me a lot of years of suffering.” She also needs help again. It’s been decades since her gastric bypass, and Lauria, now 73, hasn’t been able to keep the extra weight off. Back in 2004, she was allowed to keep her esophageal stent in for only six weeks. “I was happy because I’d started losing weight,” she says. “I’d like to have that stent back, I’ll tell you that. It works.”