Alice Mongkongllite / BuzzFeed

For years, Alicia McGarry’s elementary school–age sons tended to get sick easily. But two years ago, McGarry downloaded Sickweather, an app that broadcasts infectious illness warnings based on location-specific chatter on social media. Now, when an alert goes around, the 35-year-old mother doubles down on cold and flu precautions, reminding her boys to wash their hands and eat leafy greens. “We’ve been able to minimize family illness,” McGarry, of Kansas City, Missouri, told BuzzFeed News.

We yak endlessly on social media about our lives and the physical discomforts we sometimes encounter as we live them. We tweet about our headaches and chills, and seek solace on Facebook when we’re feverish. In doing so, we’re creating an unprecedented trove of anecdotal health data. And now researchers are digging through it to unearth some surprising things about our well-being — or lack thereof.

One of the first programs in this vein, Google Flu Trends, attempted to use aggregated search data to instantly estimate flu outbreaks worldwide, though its accuracy was questioned by some critics. That was 2008, though, and the flu was just the start. Researchers have since tapped other social media reservoirs — namely Twitter — to search for new insights into mental health, hospital admissions, heart disease mortality, and air pollution. Meanwhile, startups like Sickweather, which tracks and maps reports of illness on social media, and Iodine, which crowdsources medication reviews, are now translating digital health complaints into meaningful information for people who aren’t doctors and data scientists.

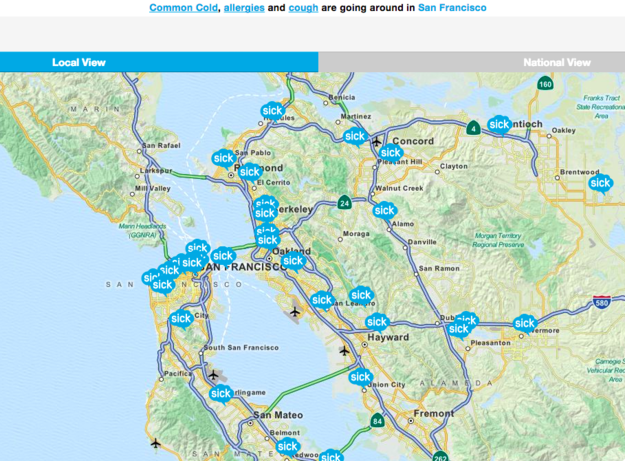

Sickweather CEO Graham Dodge claims that his app has successfully warned people about the start of flu season before the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did, and beat Chicago media in identifying whooping cough around the area. Dodge, whose background is in web development, started the company about four years ago, after he’d contracted a stomach virus and saw a friend complaining of similar symptoms on Facebook. “That’s when it occurred to me that social media could be used as a valid source of health data — if it could be mined correctly [and] you could reduce the signal-to-noise ratio,” Dodge told BuzzFeed News.

A snapshot of ailments in the San Francisco Bay Area on June 25, according to Sickweather. Sickweather / Via sickweather.com

And there is a lot of noise. That’s one reason some scientists look askance at efforts like the one Dodge is undertaking with Sickweather. Having “Bieber fever” and being “so hot right now” are clearly not clinical symptoms, though software — unaware of such colloquialisms — might flag them as such. Avid social media users also aren’t necessarily representative of the population. For those reasons, public health agencies are taking a cautious approach to social media health analytics.

“Kids under 13 aren’t allowed to sign up for [Twitter] accounts. Adults who are over 65 are less likely to be present on Twitter,” said Dr. Matthew Biggerstaff, an epidemiologist at the CDC, which has experimented with flu tracking on social media. “Those are groups where we feel like we might not be getting as complete a picture on social media as we do in our more traditional surveillance systems, where we have good coverage of all age groups in the U.S.”

Flu, stress, air pollution, and everything in between

Still, researchers’ ability to gather health knowledge from our social media updates has sharpened in the last few years — almost as quickly as social media itself has grown.

Around 2010, Mark Dredze, who specializes in computational linguistics at Johns Hopkins University, began talking to colleagues at the institution’s medical school about collaborating on a data analysis project that involved Twitter, a new microblogging service that was just starting to take off.

Dredze and his team had long relied on the news media’s coverage of current events as a proxy for health trends. “What we … used for decades is newspaper articles,” Dredze told BuzzFeed News. “We’d buy articles and that’s obviously very, very limited. And then Twitter came along [and we thought], ‘Hey, there are millions of people all over the world writing things all the time.’ That blew the mind of everyone.”

Published in 2011, the first paper from Dredze’s interdisciplinary team crunched data from 2 billion tweets to demonstrate they could chart the geographic distribution and spread of the flu in the United States between 2009 and 2010 with a degree of accuracy comparable to the CDC’s records. In one of many subsequent studies, the researchers used tweets to search for words related to anxiety, death, and negative emotions. They found, unsurprisingly, a higher incidence of tweets expressing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in U.S. military bases compared to the rest of the country.

Health-related chatter on social media can also be indicative of other health trends, researchers are discovering. A recently published analysis of Sina Weibo, China’s monster microblogging service, found a high correlation between the volume of pollution-related messages and air pollution down to the individual level of dozens of cities. And in an April study conducted by the University of Arizona, researchers analyzed Dallas-area asthma-related tweets and data from air-quality sensors to predict with 75% accuracy whether a hospital could expect a low, medium, or high number of asthma-related visits on a given day.

Another paper led by the University of Pennsylvania analyzed 148 million tweets published between 2009 and 2010 and geotagged across some 1,300 U.S. counties expressing stress and hostility. Both are risk factors for heart disease, so researchers were curious to see if there might be a link between angry outbursts on Twitter and heart-disease related deaths. Turns out there was, all the way down to the county level. In fact, the researchers found that the tweets they analyzed “predicted [atherosclerotic heart disease] mortality significantly better than did … 10 common demographic, socioeconomic, and health risk factors, including smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.”

These research efforts and the insights they’re generating — while relatively new — could someday help public health agencies better inform responses to health problems.

Johannes Eichstaedt, a researcher who helped lead the Penn heart disease study, said tweets can be a barometer for how stressed or unsafe residents feel in a community. His team is helping Mexican government officials look for social media signals in their country and combine them with census data to better understand residents’ quality of life.

Limitations

Beyond issues of linguistic nuance and demographics, mining social media for material insights into health trends can be complicated by a few other factors. Facebook posts, for instance, are often private and inaccessible. Google searches are typically cursory and can speak more to an individual’s curiosities than their actual health.

Indeed, Google Flu Trends, which promised to showcase the impact data analytics might have on public health, suffered a public chastening last year when a paper in Science criticized it for overestimating flu activity “for 100 out of 108 weeks starting with August 2011,” and described the value of the algorithm as a stand-alone flu monitor as “questionable.”

That said, the paper’s authors did note that Flu Trends might be useful if combined with other near-real-time health data, like CDC records. And, to be fair, Google and the CDC said from the beginning that Flu Trends was not intended as a stand-alone tool.

“One of the areas of confusion when Flu Trends came out is people were perceiving it not only as a replacement for the CDC system, but an oracle-type system where you could use it to develop real-time signals for any type of information,” Matt Mohebbi, one of the co-inventors of Flu Trends, told BuzzFeed News. “I think that was short-sighted.”

But Mohebbi acknowledges that Google searches aren’t perfect sources of health data for researchers. People don’t discuss some key parts of their health on those platforms, at least not in enough depth to draw any useful conclusions.

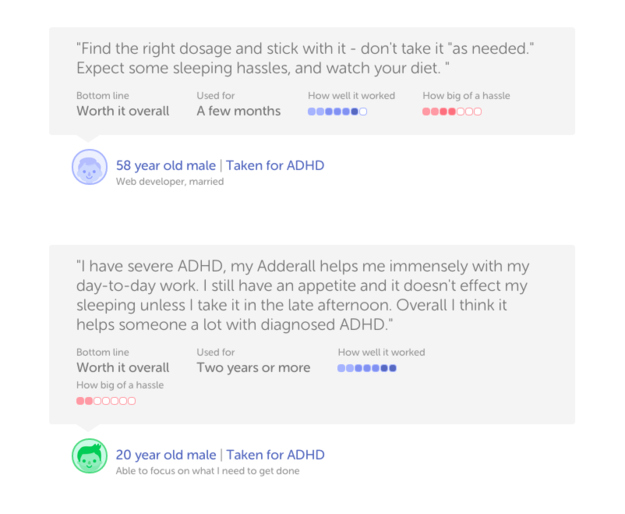

Reviews of Adderall on Iodine. Iodine / Via iodine.com

Medications

For example, there are hundreds of drugs, each with multiple names, and some of them can be prescribed for multiple conditions for which they have different efficacy rates and side effects. It’s hard to know what to expect from a prescription drug simply by searching Google or asking your Twitter followers. That’s why Mohebbi and Thomas Goetz, former executive editor of Wired, founded Iodine last year. They describe it as the “Yelp of medications.”

“We’re very specifically interested in understanding what medications are going to work best for certain individuals given their personal preferences,” Mohebbi said. “And the feeling we’ve had so far is that’s a question that can’t easily be answered through something like the search stream.”

Iodine is a searchable database of more than 100,000 consumer reviews of drugs, all filterable by age and gender. It uses natural-language processing algorithms to search medication reviews for keywords and common phrases and create a sort of drug reaction profile that can be layered on top of tips from medical experts.

This spring, the startup launched a survey asking users about their experiences with antidepressants. More than 30 million Americans take antidepressants, but the largest study to date involved just 4,000 people, note Iodine’s founders, who hope their study will help fill the knowledge gap.

Iodine isn’t exactly mining social media for health insights, but it is making good use of the same instinct that prompts us to tweet about our cold or ask Google why we’re sneezing. And, like Sickweather and Google Flu Trends, it’s using our connected world to crowdsource insights into health trends and to link our words to our wellness in the hopes of improving health care.