My mother-in-law called me yesterday. She doesn’t quite know what I do for a job but has a vague idea I work with a group seeking to understand and ultimately prevent Alzheimer’s disease.

She heard on the radio that someone had developed a cure for Alzheimer’s disease. It had something to do with cars in the driveway and the US government was bankrolling it. She was both pleased and relieved, and suggested I now focus my attention on other brain diseases that need to be cured.

She then sent me a link to the radio interview timed to coincide with the publication of research in Nature’s Scientific Reports journal. The media release about the study, like the radio interview my mother-in-law heard, was very excited.

It alerted us to an elegant set of experiments, based on technology from Flinders Medical Centre, that generated candidate vaccines against Alzheimer’s disease that may therefore provide a treatment for dementia. According to one of the study’s authors, an effective vaccine could be only a few years away.

The vaccines, tested in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and in human brain tissue, showed a high responsiveness to both targets in each context. This is indeed good news, and these compounds should be advanced to the drug-development pipeline as fast as possible.

But before we get too excited, it’s worth noting that for every 5,000-10,000 compounds that enter development pipelines, only one drug will be approved for use in patients, at an estimated cost of US$2.6 billion.

In Alzheimer’s disease specifically, 244 compounds were investigated in 413 clinical trials between 2002 and 2012, with only one new drug being approved for temporarily alleviating symptoms of the disease. That’s a success rate of 0.4%.

Some facts about Alzheimer’s and dementia

Doctors describe dementia as a phenomenon in which a person has difficulties across multiple areas of thinking. It happens, for instance, when problems in planning, remembering, concentrating or navigating become so severe that the person’s health or ability to live independently are compromised.

In people aged over 65, the most common cause of dementia (around 70%) is Alzheimer’s disease. Older age is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s; one in ten people aged between 60 and 70, and three in ten over 80, meet clinical criteria for the disease.

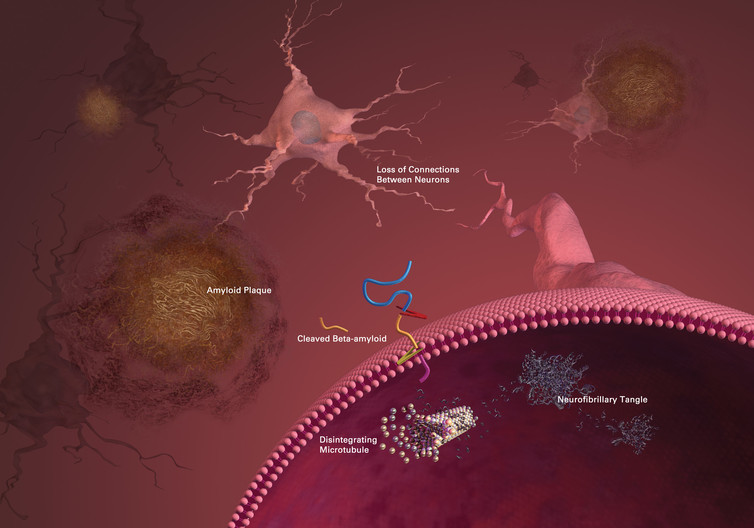

Alzheimer’s disease is named after Alois Alzheimer, who in 1906 conducted a post mortem investigation of a woman who had died with dementia. Using dyes to stain brain cells, he observed two abnormal pathological characteristics – “plaques” and “tangles” – spread throughout the brain.

These plaques and tangles remain the targets of current research. In the 21st century, the plaques are known to consist of fragments of a protein called beta-amyloid, and the tangles are known as tau proteins.

With the average age of people in developed countries increasing, so too is the number of people with Alzheimer’s disease. The great emergency is that without a breakthrough treatment, the number of people living with dementia in Australia is expected to be almost 900,000 by 2050.

With growing populations this problem becomes greater still, and the anticipated social and economic burden is considered catastrophic. Consequently, the US federal government now commits US$991 million per year to research and treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.

The Australian government has committed A$4 million a year for the next five years to overcome the same problem.

Vaccine development all over the world

There is still no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. The main treatment strategy for the past 30 years has been to try and reduce symptoms of memory loss and disorientation by replacing some of the brain chemicals, called neurotransmitters, that are lost as the disease progresses.

Like the research reported this week, we search for pharmacological breakthroughs by developing drugs to interfere with the accumulation of either the amyloid or tau proteins, or both. One way to achieve this is to use an active vaccine to stimulate the immune system to attack amyloid or tau. Alternatively, artificial antibodies against amyloid or tau can be given regularly via infusions. This is known as a passive vaccine.

At least 14 vaccine development programs targeting tau are currently underway. For amyloid, at least 18 vaccine programs have begun or have been completed and failed.

Other, non-vaccine treatments against amyloid and tau are also in development. For example, drugs may aim to remove the amyloid or tau or to stop their formation to begin with.

There is other good news that suggests we are getting closer to treating Alzheimer’s disease. A recent re-analysis of data from some large, but failed, clinical trials of an amyloid vaccine called solanezumab showed beneficial effects in a subgroup of patients.

Another amyloid vaccine, aducanumab, was recently shown both to remove amyloid and to improve thinking in people with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Both of these vaccines are being investigated in Australia and people who would like to find more information on them can contact their doctor or our research laboratories.

Obviously, the more shots on goal the better. Success in human drug development is painfully low. Pharmaceutical industry estimates suggest the development of a new drug is estimated to require at least 10-15 years.

Despite my mother-in-law’s suggestions, I still turned up for work today. While I hope these new vaccines are effective there is a high probability they will fail to hit their target in living humans, or they will hit the target but in doing so make people sick for other reasons. Or maybe the target is wrong altogether. So it isn’t the time to focus elsewhere just yet.

Paul will be online for an Author Q&A between 3 and 4pm on Friday, July 15, 2016. Post any questions you have in the comments below.

![]()

Paul Maruff receives funding from the CSIRO Flagship Collaboration Fund and the Science and Industry Endowment Fund (SIEF) in partnership with Edith Cowan University (ECU), Mental Health Research institute (MHRI), Alzheimer’s Australia (AA), National Ageing Research Institute (NARI), Austin Health, Macquarie University, CogState Ltd., Hollywood Private Hospital, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Dementia Collaborative Research Centres program (DCRC) and Operational Infrastructure Support from the Government of Victoria. Paul Maruff is also an employee of Cogstate Ltd (ASX:CGS).