GlaxoSmithKline and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, have a 50-50 partnership in the new company.

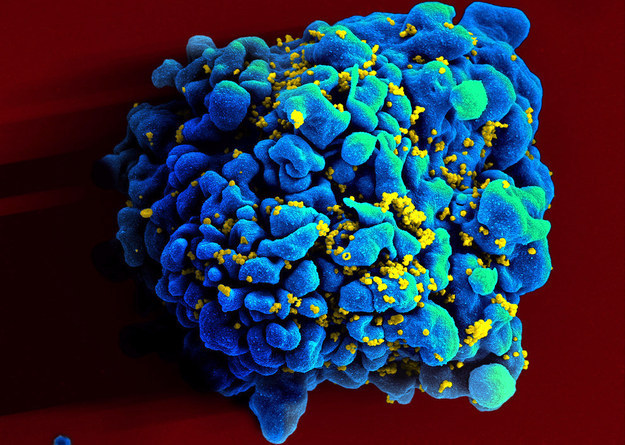

A blood cell infected with HIV. NIAID / Via Flickr: niaid

A large drug company and a public university have launched a new company with the goal of not just treating, but curing HIV.

British health care giant GlaxoSmithKline has pledged $20 million over five years and roughly 10 of its scientists to the new effort. Its partner, the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, will contribute about 40 researchers, as well as access to patients at its hospital for clinical trials and laboratory space on its medical campus.

Companies and universities routinely collaborate on scientific research. They’ll license each other’s technologies, and universities will even create startups to commercialize the ideas of its researchers. But the new company, named Qura Therapeutics, appears to be the first example of public and private science going into business together and splitting future profits equally.

The partnership is especially notable because it’s not based on any specific invention or technology. “This sounds very open-ended, and I think this part of it is kind of unusual,” Kenneth Kaitin, director of the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, told BuzzFeed News.

The cultures of big pharma and academia are strikingly different, Kaitin added, often making it difficult to work out mutually agreeable terms. But with government funding of scientific research in a decade-long slump, Kaitin says we’re likely to see the private sector get more involved — in all sorts of ways. “Nothing is surprising to me anymore in terms of these relationships.”

HIV/AIDS patient Michael Willis of Baltimore sorts out his medicine in 1998. Roberto Borea / Associated Press / Via apimages.com

Both GSK and UNC-Chapel Hill have a long history investigating HIV/AIDS.

The first approved drug for HIV, azidothymidine or AZT, was patented in 1985 by Burroughs Wellcome, which was subsequently acquired by GSK.

At UNC-Chapel Hill, molecular biologist David Margolis and his colleagues have made headlines for their strategy to root out HIV from its many hiding spots (known as “latent reservoirs”) in the body — even in patients already treated with antiretroviral therapy.

With that line of research, “what was once provocative and unthinkable became mainstream: let’s try and cure AIDS,” Myron Cohen, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at UNC-Chapel Hill, told BuzzFeed News.

That scientific strategy, informally known as “shock and kill,” will be at the center of the GSK-UNC collaboration.

The leaders of the new effort recognize that their initial investment is fairly small, on the scale of what it takes to develop a new drug. They hope to be a catalyst for more funding — from the government and, perhaps, from other companies — later on.

“Clearly $20 million is not enough to get a cure,” Zhi Hong, head of the Infectious Diseases Therapy Area Unit at GSK, told BuzzFeed News. But “it’s good enough to get things started.”

Traditionally, university scientists have focused on basic research, whereas industry scientists turn these big ideas into commercial products.

“The academic model lends itself to serendipity, and the industry model doesn’t,” Kaitin said. “It’s been weeded out of industry because of the economic and financial demands on the companies.”

Industry desperately needs those new ideas to fuel its drug pipeline. Medical researchers at universities, meanwhile, don’t want their ideas confined to the laboratory, and need industry’s knowledge of scaling and standardization to make them a reality for patients.

So why aren’t these public-private deals more common?

“The two major stumbling blocks that I’ve seen over the years are essentially money and glory,” Arti Rai, a law professor at Duke University, told BuzzFeed News.

Money comes from patents and proprietary knowledge about specific drugs or technologies. “A lot of pharmaceutical companies find that, from their standpoint, universities seem grabby,” Rai said. “And the universities, vice versa, say the pharmaceutical companies are grabby.”

Power, in academia, comes from publishing scientific findings — generally as much and as soon as possible. But that’s troubling, from an industry perspective, because publishing information too quickly may mean giving up patent rights.

Despite these challenges, pharma-university partnerships are happening more and more. In 2010, for example, Pfizer launched its Centers for Therapeutic Innovation, which gives grants to academic researchers to work in Pfizer labs, with access to Pfizer’s drug libraries. And in 2012, the University of Pennsylvania teamed up with Novartis to commercialize Penn scientists’ work on immunotherapy for cancer.

As for the new Qura Therapeutics, any future profits will be split down the middle between UNC-Chapel Hill and GSK, according to GSK’s Hong. And researchers will have no restrictions on what they can publish or how quickly they publish it.

In the long term, however, the consequences of these academic-industry relationships may not all be so rosy.

What would happen to academia’s freedom and serendipity if basic researchers were suddenly driven to make all of their experiments lead to something marketable? “There’s an advantage to freeing up academics to be able to explore research questions without the inhibition of thinking of a quarterly financial statement,” Kaitin said.

There are serious worries about ethics and credibility, too. Researchers who are sponsored by industry may be inclined — consciously or not — to steer their work toward what their funder wants. And even if their science is not biased, the public may perceive it to be.

“I think in general it is the case that people are often more suspicious of pharmaceutical company research than they would be of purely public funded research,” said Duke’s Rai. “A pharmaceutical company obviously has an interest in a certain result.”