Her answer shows the power of a trusted doctor.

Virginia Hughes

People are always shocked to learn that I wasn’t vaccinated as a baby. I’m a science journalist, after all, and studied neuroscience in college. I believe in science, and science is unequivocal about whether babies should be vaccinated: They should be.

But my parents weren’t so enamored with mainstream scientific authorities. We lived in a small town in rural Michigan, where my mom had also grown up and where everybody knew everybody else’s business. We nominally had a family doctor — Dr. Burris, an osteopathic physician — but I don’t remember ever going to see him as a kid, or ever being sick at all. (Once when I was 5 or 6, according to my mom, I came down with a bad cold, and my nanny threatened to quit if my parents didn’t take me to a doctor. So I went, got antibiotics, and was fine.)

I didn’t realize that being unvaccinated was odd until grade school, when my parents had to sign a form saying they objected on religious grounds. When I was 16, I had to get a tuberculosis skin test in order to volunteer at a nursing home, and at 17, I had to get a series of shots so that my college would let me live in the dorms. Otherwise, though, it rarely came up.

I haven’t thought much about my vaccination history until this week, while covering the for BuzzFeed News. I realized that I’d never actually asked my parents why they didn’t vaccinate me or my younger sister.

I knew it wasn’t because of the (now thoroughly debunked) link between autism and vaccines; that research didn’t make headlines until 1998, and I was born in 1984. I figured my parents’ choice boiled down to their politics, which were of the conservative/libertarian/small-government variety. They were those people who refused to give Social Security numbers to anybody, for any reason. With a handful of like-minded friends, they created a group, called “Citizens for Improved Government,” and published a newsletter taking aim at what they saw as an overreaching city government and school board.

It was fitting, I thought, that they refused state-mandated vaccinations, the most pervasive and successful public health strategy of all time. But I didn’t know for sure. So I emailed my mom to request an on-the-record interview, and she readily agreed. After some small talk, we got around to the Disneyland outbreak.

“They’re trying to connect it to the conservatives — it’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever seen,” she said over the phone. “It’s the vegetarian people and the ultimate hippies who started the movement, and they’re all liberals! It’s not a political thing anyway; it’s ridiculous.”

I told her about my assumption — that her stance on vaccines came out of libertarian values. Was that true?

No, she said, that wasn’t it at all. “I was totally pro-vaccines, really, until Dr. Taylor.”

Dr. Taylor was my parents’ dentist. He was part of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which was somewhat unusual in our town. “They look at things differently,” mom said. “They’re vegetarians.” My parents were decidedly not, but they respected this guy because he was well-educated.

A month after I was born, my parents took me to meet Dr. Taylor. He gave them a brand-new book, called How to Raise a Healthy Child in Spite of Your Doctor, written by a medical doctor named Robert S. Mendelsohn. The book seems to be a favorite among the alternative-medicine crowd, and Mendelsohn, a self-described “medical heretic,” was apparently against heart surgery, water fluoridation, and “modern medicine.”

That book changed everything, mom said. “There were a couple of chapters on immunizations, and that was what we zeroed in on.”

Listening to her rattle off the book’s specific claims about vaccines, I was surprised at how much time and consideration she had put into thinking through the data — or at least the data she knew about. Dr. Burris, an osteopathic physician who “was not into meds,” my mom said, was also sympathetic to Mendelsohn and Taylor’s ideas. In other words, all of the experts my parents knew and trusted were steering them against vaccines.

But they didn’t just make a blanket decision about all vaccinations. When considering the MMR vaccine — a combination jab for protection against measles, mumps, and rubella — mom and dad analyzed the risk-benefit ratio of each disease, one at a time.

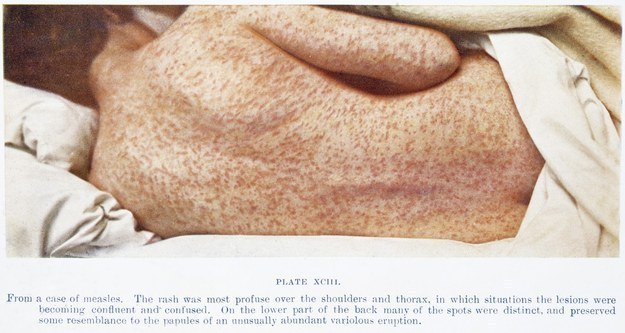

Wellcome Library, London / Via wellcomeimages.org

Measles was an easy no for them, my mom said. “We all had the measles, before they had the shots. It went through the whole community, and it didn’t hurt anybody.” She remembered having the characteristic red rash, and missing a week of school while holed up in her room with the shades drawn. And yet, she said, “I’m sure there’s something good about them — they helped me build some immunities or something.”

This idea of measles as a mild disease is . The virus isn’t likely to kill, but it makes kids miserable. And it can lead to terrible complications: 8% of cases get diarrhea, 7% an ear infection, and 6% pneumonia. About 1 in 167 will get seizures, and 1 in 1,000 swelling of the brain.

Mumps, mom continued, was also an easy choice, because the virus was only really a problem for boys. This is not really true. Mumps is a somewhat benign virus; about half of all people who get the mumps won’t develop any symptoms. But the other half will get a fever, headache, exhaustion, and swollen glands. Adolescent boys, as mom noted, may develop inflamed testicles. In rare cases girls, too, can develop inflammation in their breasts and ovaries.

But even she acknowledged that rubella was much more serious. She knew that if a pregnant woman contracted this virus, there was a very high risk of her baby having birth defects. The reason she didn’t vaccinate me against rubella as an infant, she said, was so that I would be more likely to get a shot later. “Otherwise, the kid assumes they’ve got a lifelong immunity, and she doesn’t necessarily get a booster during her childbearing years, when she needs it the most.” To me, that sounds like twisted logic, but it was her logic.

The DPT vaccine — for diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus — was more complicated. Diphtheria, a bacterial infection that affects the respiratory tract, has long been eradicated in the United States. “Diphtheria is pretty much unheard of anymore, so we figured we didn’t need that,” she said.

Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a bacterial infection that can be deadly for young babies, mom acknowledged. (In 2012, in fact, a pertussis outbreak killed 20 people, and most were infants younger than 3 months.) But the pertussis vaccine, according to her new book, was perhaps equally dangerous. “I think I read that it caused mental retardation within two hours,” she told me. (This is not true.)

Tetanus, though, my parents were absolutely worried about — they had seen for themselves the lockjaw it causes. And so, mom said, they went to Dr. Burris with their decision: They wanted me to get just one vaccine — one specifically for tetanus, instead of the DPT combo — and none of the others.

Dr. Burris had to special-order the tetanus-only vaccine, which led to my parents receiving a call from a public health nurse. “They thought we were poor and we couldn’t afford the shots,” mom said. Eventually the shot came, and my mom took me to the doctor’s office. By then I was about 5 months old. “I had to look away when you even got that tetanus. I felt like leaving the room with the doctor there, poking you with that needle.”

Wikipedia / Via upload.wikimedia.org

I asked her whether she had read my about the harms of measles. She hadn’t, so I summed it up. Why, I asked, wouldn’t you want to avoid putting your kid through all that pain? “We figured everybody else was immunized, and so there’s no way you would catch it from anybody.”

And that, of course, is the crux of the problem. When is high, there isn’t a pressing reason for any given individual to be vaccinated. At the time, she thought vaccines came with scary side effects. So why would she risk it, no matter how small that risk? But that creates a dangerous paradox: If everyone made the choice she did, then everyone would get very, very sick.

My mom knows that I don’t agree with her about the dangers of vaccines. And, after reading some of my articles and others over the years, she seems to be less worried about vaccines than she used to be. Still, she doesn’t regret her choice.

“That book, talking about what was happening to those babies after a pertussis vaccination, it was just…” she paused. “Maybe it’s all a fable, I don’t know, you know how this stuff gets started.

“But when you have a baby you feel differently than before you have children. You are responsible — this is your baby! You look at things differently than you would as a concerned scientist.”

The conversation was revelatory for me, for two reasons. First, it made me wonder whether vilifying anti-vaccine parents — as the press has done repeatedly this week — is a good strategy for increasing vaccine coverage. When parents make medical choices, good or bad, it’s for one simple reason: They’re trying to do the right thing for their kid. Refusing vaccination is not a political statement.

Second, my mom’s story illustrates that data and authority and expertise can have real power, but only when communicated effectively. For whatever reason, the ideas of Dr. Burris, Dr. Taylor, and Dr. Mendelsohn resonated with my parents in a way that mainstream medical voices did not. Why? This is the question I wish more doctors would ask — and more journalists too. If we did, then maybe we’d better understand how fables about modern medicine are written. And, perhaps, how to erase them.