Dark clouds hung over smoking as a likely risky activity long before the watershed case control studies on smoking and lung cancer were published in 1950 by Doll and Hill (on British smokers) and Wynder and Graham (on American smokers).

Early last century Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the boy scouts movement wrote with sexist prescience:

When a lad smokes before he is fully grown up it is almost sure to make his heart feeble, and the heart is the most important organ in a lad’s body.

Popular expressions such as “smoking stunts your growth” derive from that period.

The commonplace of smokers’ cough had always quietly worried people that filling their lungs with smoke some twelve times per cigarette, sometimes up to 60 cigarettes a day, every day of the year for many years might be a problem.

As far back as the 1920s, Lucky Strike advertised that it was “less irritating” to the throat.

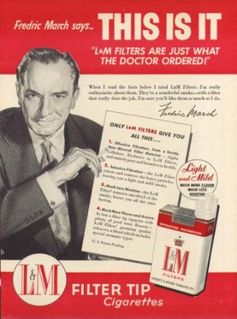

Following a series of widely read articles in the Readers’ Digest on cancer and smoking, filters on cigarettes first began being introduced in the late 1940s and were accompanied by uninhibited claims about risk reduction (“L&M filters are just what the doctor ordered!”). The goal was smoker reassurance. This was the start of a global industry program designed to keep anxious smokers from quitting – and it continues today.

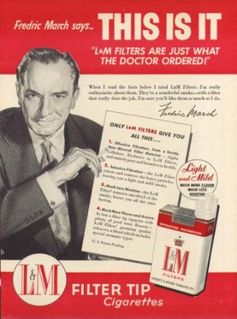

The most outrageous innovation in tobacco harm-reduction was Kent’s micronite filter, which used deadly blue asbestos (crocidolite) between 1952-56 in the United States (see the Kent micronite filter advertisement below).

Decades of litigation followed, with the most recent in Florida with US$3.5m awarded against the manufacturers. I’ve found evidence that Kent with the micronite filter was sold in Australia in 1961, although we don’t know if it still contained asbestos.

An unforgettable demonstration of what gets through cigarette filters can be seen here. Mike Atrix, filming in Sydney, compares the brown stains exhaled into a tissue paper from holding the cigarette smoke in his mouth and also after exhaling it after pulling it into his lungs.

Two things are very obvious: the filter on the cigarette allows obvious quantities of particulate matter (“tar”) through and into the lungs, and the lungs retain considerable amounts of these toxic particles when the smoker exhales.

But the mass migration to filtered cigarettes did nothing to prevent a progressive increase in lung cancer risk among male smokers who began smoking during and after the second world war compared to the first world war-era smokers. A critical review of the evidence that so-called reduced-risk cigarettes lowered tobacco-caused death rates concluded:

that lung cancer risk continued to increase among older smokers from the 1950s to the 1980s, despite the widespread adoption of lower yield cigarettes.

The change to filter tip products did not prevent a progressive increase in lung cancer risk among male smokers who began smoking during and after the second world war compared to the first world war era smokers…

No studies have adequately assessed whether health claims used to market “reduced yield” cigarettes delay cessation among smokers who might otherwise quit, or increase initiation among non-smokers.

There is no convincing evidence that past changes in cigarette design have resulted in an important health benefit to either smokers or the whole population.

Tobacco control policies should not allow changes in cigarette design to subvert or distract from interventions proven to reduce the prevalence, intensity, and duration of smoking.

Between 1968 and 1980, the US National Cancer Institute invested more than $US50m into research on less hazardous cigarettes. But by 2001, it had concluded that there was no evidence that smokers switching to so-called less hazardous cigarettes (lights and milds) had a lower rates of disease or death.

Unlike cigarette testing machines, which were calibrated to smoke the putative reduced-risk cigarettes in a standardised way, smokers compensated for the lower delivery of nicotine by taking more and deeper puffs per cigarette, smoking more and occluding the tiny ventilation holes on the filters with their fingers.

These holes let air in to dilute the smoke pulled through into the testing machines, providing the tar and nicotine readings that were not those that smokers actually obtained from smoking. Around 78% of Australian smokers bought light or mild-labeled brands before these descriptors were banned by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission as misleading in 2005.

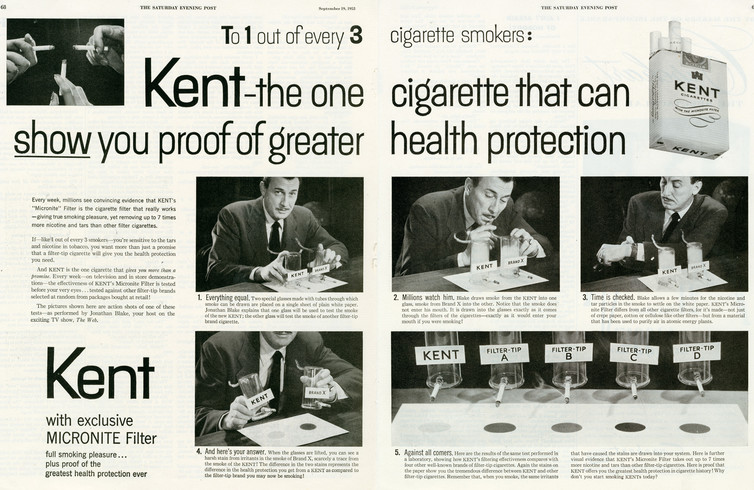

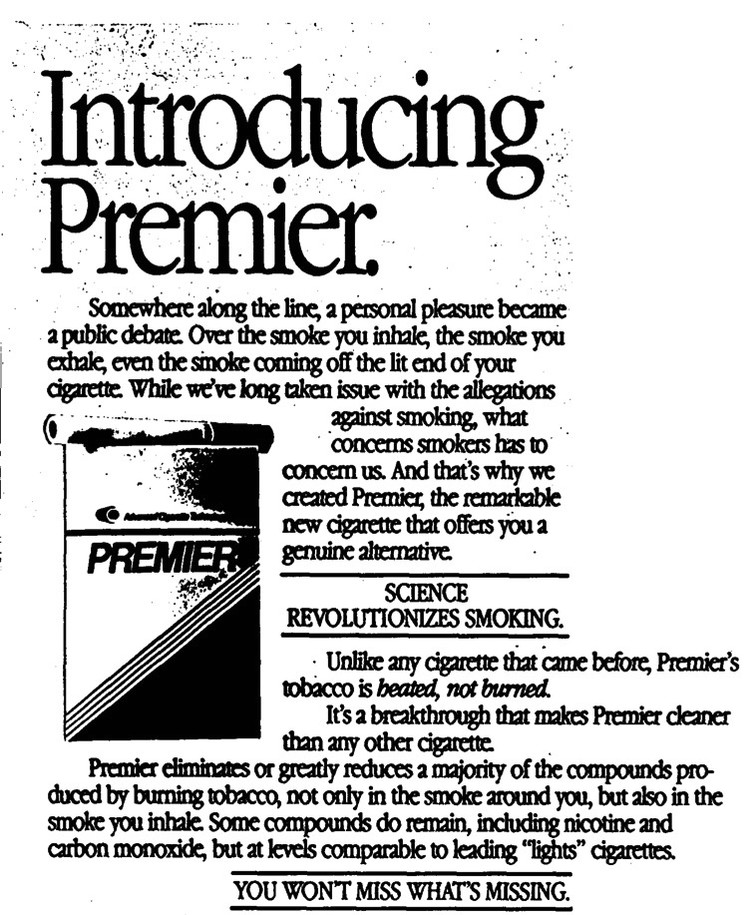

In more recent years, we saw a series of failed attempts by tobacco companies to interest smokers in switching to “reduced carcinogen” cigarettes such as Omni (see the ad below) and products which heated rather than burned tobacco (“Introducing Premier, the remarkable new cigarette that offers you a genuine alternative”), delivering a vapour into smokers’ lungs.

These products have all been abject market failures and because of this, no longitudinal data exist on whether they actually reduced harm in users.

E-cigarettes are the latest kids on the tobacco harm-reduction block, although their users insist they are not tobacco, smoking or cigarettes.

Like all their predecessors, their promoters have graduated from hype school. All good news is megaphoned, and all questioning pilloried as thousands of tiny start-up manufacturers, retailers and their PR agencies try to catch the wave, along with all the major tobacco companies which are now selling both e-ecigarettes and tobacco products.

E-cigarettes have only been in widespread use in early adopting nations for just a few years. Respiratory and heart diseases and cancers caused by tobacco use generally take several decades to manifest, which is why the jury on reduced-risk cigarettes was out for so long before declaring them failures.

Those who insist they are “95%” less dangerous are therefore only making fingers-crossed predictions, much in the same way that the scientific colossus Ernst Wynder (who published the first case control study on smoking and lung cancer) did about his hopes for reduced-risk cigarettes. Wynder was wrong.

The failure of all previous tobacco harm-reduction efforts does not mean that all current or future efforts will also be failures, or worse, slow or reverse the 50-year fall in smoking prevalence. But this history should serve as a dazzling warning light to switch on the bovine excrement detector and remain hyper-vigilant over the often gossamer-thin claims that abound about both their safety and how good they are at getting smokers to switch completely.

For example, efforts to liken the risks of vaping to breathing steam in a shower distract from the emissions containing nicotine, carbonyls, metals, and organic volatile compounds. Moreover, the high concentrations of nanoparticles in vape, despite their small mass, may have a significant toxicological impact because of their increased ability for deep penetration into the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems.

Recent reports of rapid onset changes in aortic stiffness after exposure to vape, of mice exposed to vape with nicotine developing features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and the suppression of immune and inflammatory-response genes in nasal cells are examples of possible early causes for concern. With vapers taking an average of 200 puffs per day (and up to 610) – some 73,000 deep inhalations each year – vapers’ exposures over many years will be considerable.

There are now more than 8,000 different flavours available through e-cigarette suppliers. The 2016 revised statement on e-cigarettes by the US Flavoring and Extract Manufacturers Association about these chemicals (which have been safety assessed for use in foods and beverages, but not for inhalation) is further cause for concern:

The manufacturers and marketers of e-cigarettes and all other flavored tobacco products, and flavor manufacturers and marketers, should not represent or suggest that the flavor ingredients used in these products are safe because they have FEMA GRASTM status for use in food because such statements are false and misleading.

It would be unequivocally great news if time shows e-cigarettes to be both all but benign and effective at helping smokers quit. Such a benevolent genie let out of the bottle would be good news. But if the genie starts looking like a trojan horse bringing its very own set of health problems down the track, addicting vast numbers of school kids to nicotine who would have never used any nicotine product, and slowing smoking cessation through prolonged dual use of e-cigs and cigarettes, putting it back in the bottle may prove very hard.

That’s why most Australian health agencies are urging the Therapeutic Goods Administration to think very carefully before letting e-cigarettes off the leash.

![]()

Disclosure

Before retiring from employment with the University of Sydney the author contributed to an options paper on the regulation of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems commissioned by the Department of Health, Canberra. He wrote a first draft of a section on their use in smoking cessation.